What’s the diagnosis?

Multiple scaly plaques on the head and arm

Case presentation

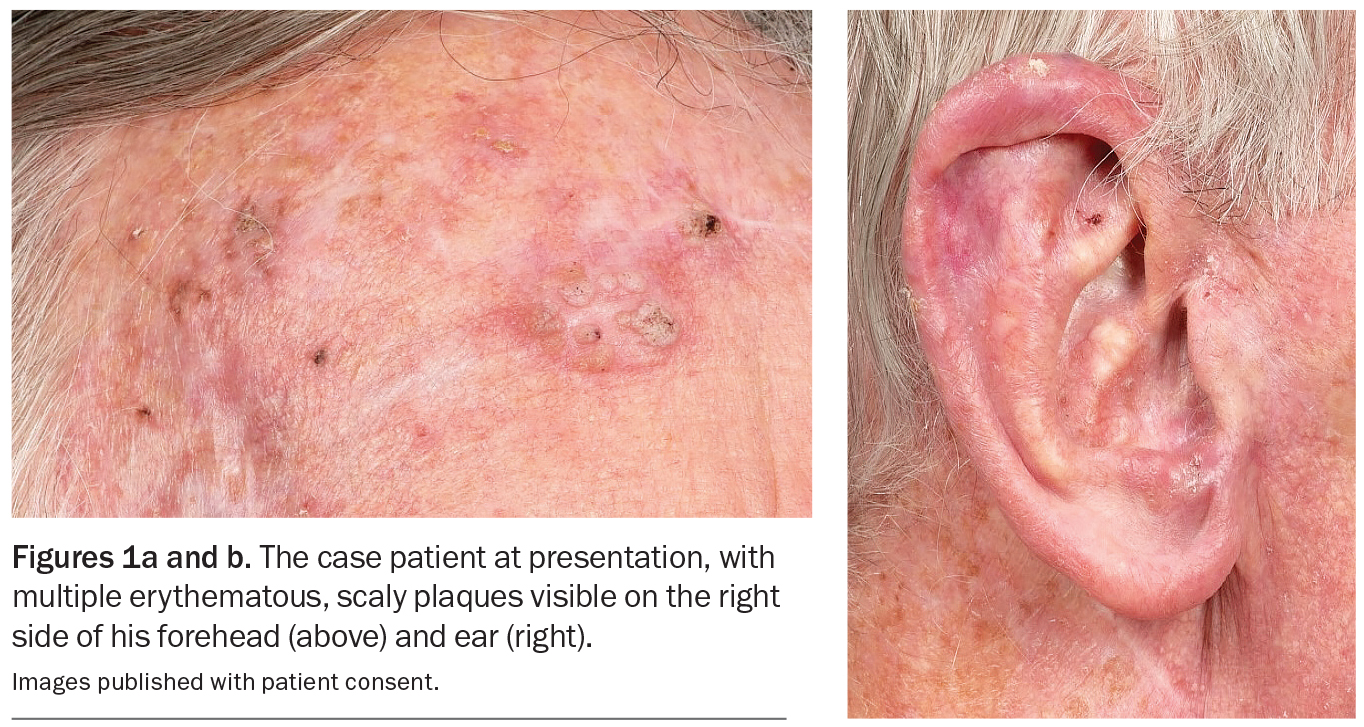

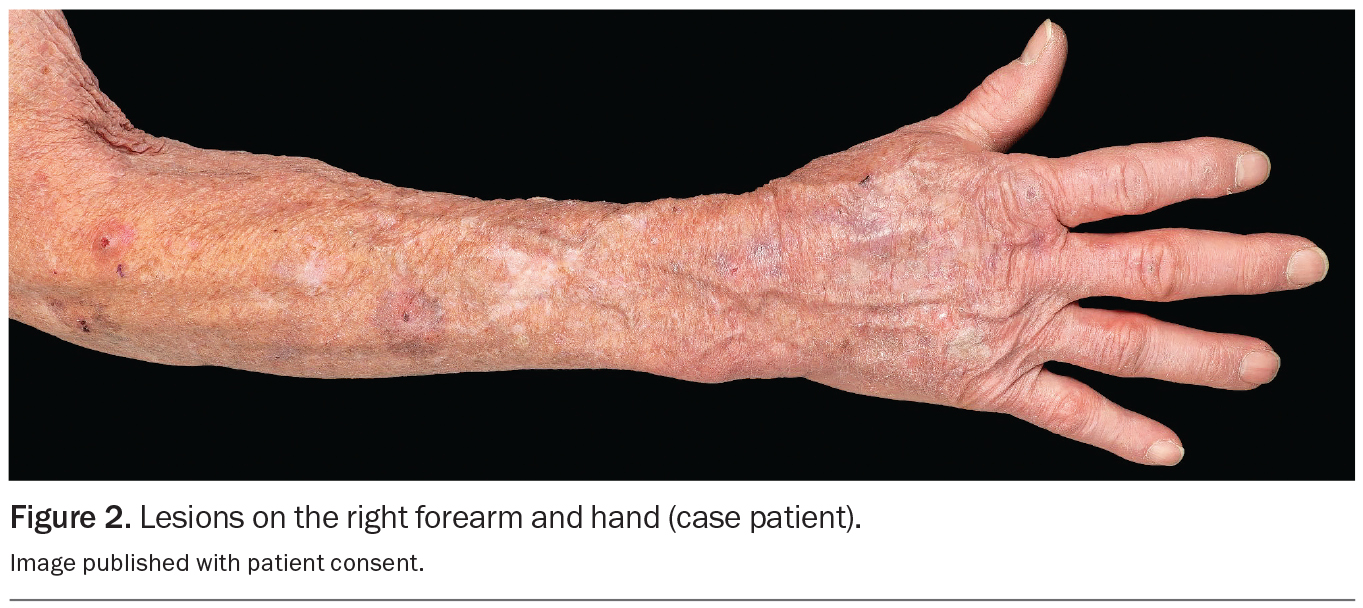

An 80-year-old Caucasian man presents for his annual full skin examination. He has scaly plaques over sun-exposed areas, including his head (Figures 1a and b) and arm (Figure 2). There is no tenderness or itch associated with the lesions.

The patient had a squamous cell carcinoma excised from his scalp two years previously. He has no history of immunocompromise or use of photosensitising medications. He denies a family history of melanoma or other skin cancer.

The patient is otherwise well and taking no regular medications. Before retirement, he worked as a builder and he still enjoys playing golf.

On examination, multiple scaly plaques are observed on the right side of the patient’s face and the dorsum of his right hand and forearm. A background of sun-damaged skin is noted. There is no associated cervical, axillary or inguinal lymphadenopathy. He has Fitzpatrick skin type 2.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ, which is also known as intraepidermal SCC or Bowen’s disease, is considered to be a premalignant lesion. If left untreated, it has the capacity to progress to an invasive malignancy; however, this is rare (published rates are between 3% and 5%).1 SCC in situ presents as a plaque that is red, scaly and crusty and often asymptomatic. Sun-exposed areas, such as the upper or lower limbs, are typical locations. A skin biopsy may be needed to establish a diagnosis.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Cutaneous SCC (cSCC) occurs when dysplastic squamous cells invade the dermis. They typically present as progressively enlarging hyperkeratotic nodules that can be tender or indurated and are often ulcerated. The diagnosis is usually clinical and can be confirmed by biopsy. High-risk SCCs include lesions that are located

on mucosal surfaces, such as the lips or genitalia, as these have a strong propensity to metastasise, particularly in patients who are immunosuppressed.2,3

Superficial basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer arising from the basal cells of the epidermis. Clinically, a superficial BCC can resemble an SCC in situ as a small erythematous plaque with associated ulceration; however, a BCC may have a visible shine over its surface. Superficial BCCs tend to ulcerate and are not usually scaly. They tend to be locally invasive but metastasis is rare.

Nodular basal cell carcinoma

A nodular BCC typically presents as a slow-growing, pearly, elevated nodule that can bleed and ulcerate centrally and has a surrounding fleshy, shiny rim. They commonly arise on the face, particularly on the nose or near the eyelids, and are usually solitary. Arborising telangiectasia can be noted on dermoscopic examination, which is pathognomonic for BCC.

Seborrhoeic keratosis

Seborrhoeic keratosis is a common benign cutaneous eruption associated with increasing age, the cause for which is unknown. The clinical presentation can vary but they often occur as a warty solitary plaque or as a papule. The hallmarks of seborrhoeic keratoses include fissures, furrows forming a cerebriform pattern, white milia-like cysts and comedo-like openings, which can all be visualised on dermoscopy.

Actinic keratosis

This is the correct diagnosis. Actinic keratosis (AK), also known as solar keratosis, is a lesion that manifests following cumulative exposure to UV radiation, which causes irreversible DNA damage within keratinocytes. Australia has the highest prevalence of AK, where it is estimated to affect more than 40% of adults over the age of 40 years.4,5 Risk is increased for Caucasian people (Fitzpatrick skin type 1 and 2) and people who live in close proximity to equatorial regions, where there is greater exposure to UV radiation.6 Increasing age, male sex, immunocompromise, photosensitising drugs (e.g. azathioprine) and occupational exposure to arsenic are other risk factors. Solid organ transplant recipients are up to 250 times more likely to develop AK.7

AK has a predilection for sun-exposed areas of skin. Commonly affected sites include the face (particularly the nose), the upper and lower limbs, including the dorsum of the hands and feet, and the scalp in bald men.

The clinical appearance of AKs can vary significantly, both within and between individuals, often making this common condition a challenging diagnosis.8 Clinically, AK can present as a macule or a hyperkeratotic palpable plaque or papule on a background of normal skin or on skin that has a confluent erythematous appearance due to chronic sun damage. There is variation in the colour of AKs – lesions can be flesh-coloured, inflamed or erythematous or, rarely, associated with pigment.9 The consistency of the lesions can also vary, being associated with a slight scale, often resembling a wart in appearance.

Clinically, there is thought to be a continuum between actinic keratosis, SCC in situ and cSCC; however, progression is uncommon. The risk of malignant transformation of AK to SCC within one year is reported to be less than 1 in 1000.10 Untreated, the majority of AKs remain stable or regress.9,10 On examination, SCC in situ tend to be more plaque-like and prone to bleeding than AKs. Tenderness is uncommon for AK but cSCC are often tender.

Management

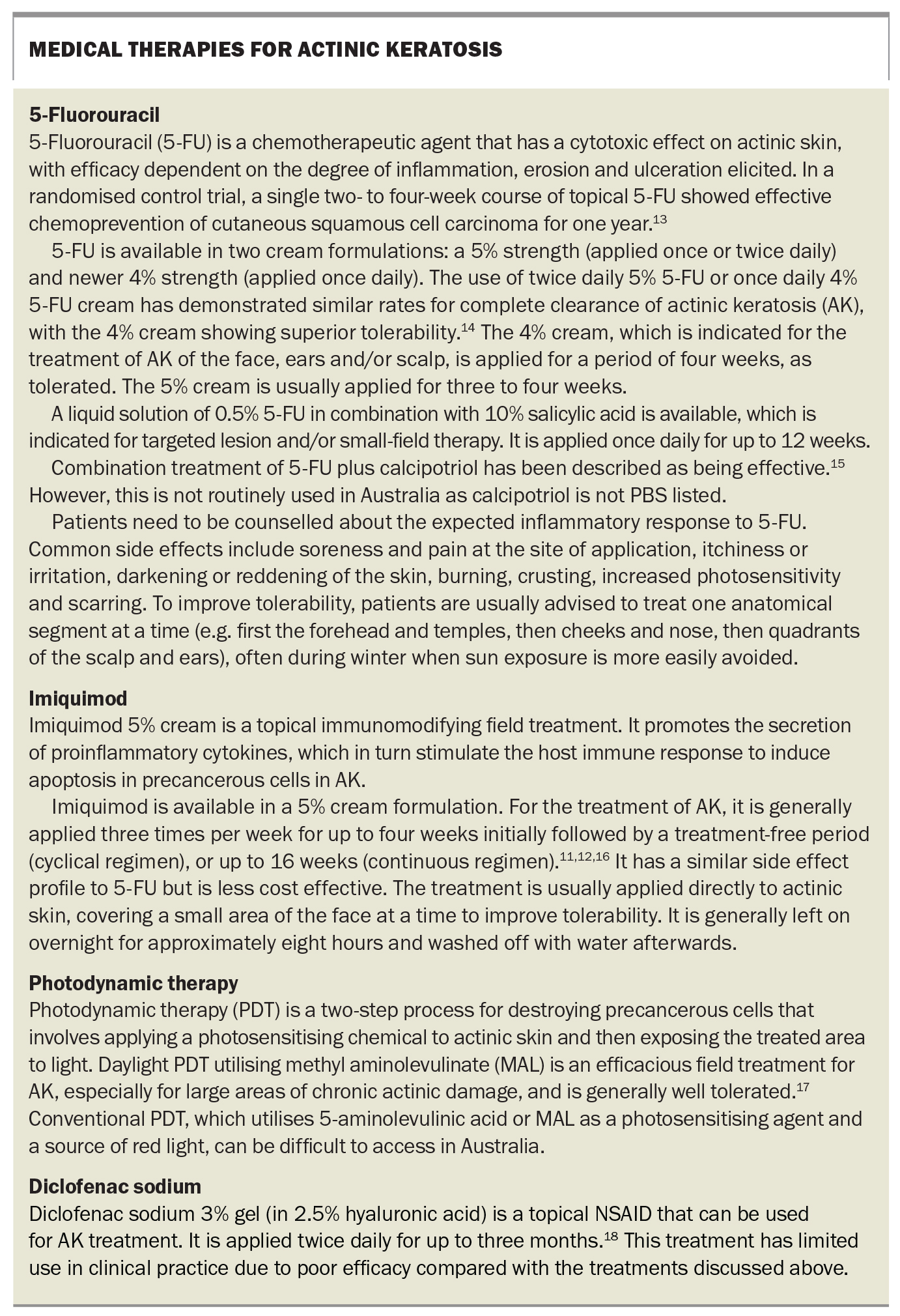

Evidence-based treatment for AK is informed by Cancer Council Australia’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Keratinocyte Cancer and the American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines of Care for the Management of Actinic Keratosis.11,12 Both physical and medical therapies are used to treat AK. The main goals are to treat symptoms and to improve cosmesis.

Cryotherapy, ideally with a liquid nitrogen spray, is a practical and efficient treatment option for AK.12 It is important to note that lesions will recur as a rule. Routine excision of AK is not generally recommended.

Medical therapies for AK are listed in the Box.11-18 For patients whose lesions are widespread and resistant to previous treatment, a field therapy will be the treatment of choice. Addition of a keratolytic agent (e.g. 10% salicylic acid) can improve penetration.

In addition, patients should be counselled about the need for sun protection. This includes wearing long-sleeved, dark-coloured clothing with a close weave and broad-brimmed hats and applying sunscreen. Patients should be informed that regular use of sunscreen not only prevents the development of AK, but also enhances the remission of existing lesions.19

Outcome

For the case patient, the diagnosis of AK is consistent with his history of significant cumulative sun exposure. He recalls blistering sunburns as a child growing up in Victoria, and he had an outdoor occupation and sporting hobby. At the time of this presentation, his AKs had been treated with cryotherapy over a period of years, but the lesions were recurring and increasing in number.

As the patient’s AKs were resistant to previous cryotherapy and he had widespread actinic damage, a field therapy was selected. He commenced treatment with 5% 5-fluorouracil, to be applied once daily for four weeks during the winter months, and advised to treat one area at a time (first the forehead and temples, then the cheeks and nose, then the quadrants of the scalp and ears, and then the right hand and arm), to eventually cover all areas of concern. He was counselled about the expected inflammatory response and need to avoid sunlight exposure because of the photosensitising nature of the cream. He was also given advice about sun protection, including the regular use of SPF50+ sunscreen, to optimise his clinical response, and encouraged to continue his annual skin-cancer surveillance. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Tokez S, Alblas M, Nijsten T, Pardo LM, Wakkee M. Predicting keratinocyte carcinoma in patients with actinic keratosis: development and internal validation of a multivariable risk-prediction model. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183: 495-502.

2. Wheller L, Soyer HP. Clinical features of actinic keratoses and early squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol 2015; 46: 58-63.

3. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26: 976-990.

4. Marks R. Epidemiology of non-melanoma skin cancer and solar keratoses in Australia: a tale of self-immolation in Elysian fields. Australas J Dermatol 1997;

38 Suppl 1: S26-S29.

5. Chetty P, Choi F, Mitchell T. Primary care review of actinic keratosis and its therapeutic options: a global perspective. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2015; 5: 19-35.

6. Chia A, Moreno G, Lim A, Shumack S. Actinic keratoses. Aust Fam Physician 2007; 36: 539-543.

7. Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Comparative epidemiologic study on premalignant and malignant epithelial cutaneous lesions developing after kidney and heart transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 33(2 Pt 1): 222-229.

8. Rosen T, Lebwohl MG. Prevalence and awareness of actinic keratosis: barriers and opportunities. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68(1 Suppl 1): S2-S9.

9. Moy RL. Clinical presentation of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42(1 Pt 2): S8-10.

10. Marks R, Foley P, Goodman G, Hage BH, Selwood TS. Spontaneous remission of solar keratosis: the case for conservative management. Br J Dermatol 1986; 115: 649-655.

11. Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer

v1.4. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia; 2024. Available online at:

https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/skin-cancer/keratinocyte-cancer (accessed October 2024).

12. Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85: e209-233.

13. Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream:

a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 167-174.

14. Dohil MA. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of 4% 5-fluorouracil cream in a novel patented aqueous cream containing peanut oil once daily compared with 5% 5-fluorouracil cream twice daily: meeting the challenge in the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol 2016; 15: 1218-1224.

15. Mohney L, Singh R, Grada A, Feldman S. Use of topical calcipotriol plus 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol 2022; 21: 60-65.

16. Chen K, Yap LM, Marks R, Shumack S. Short-course therapy with imiquimod 5% cream for solar keratoses: a randomized controlled trial. Australas J Dermatol 2003; 44: 250-255.

17. See J-A, Shumack S, Murrell DF, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of daylight photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevinate cream for actinic keratosis in Australia. Australas J Dermatol 2016; 57: 167-174.

18. Nelson C, Rigel D, Smith S, Swanson N, Wolf J. Phase IV, open-label assessment of the treatment of actinic keratosis with 3.0% diclofenac sodium topical gel (Solaraze). J Drugs Dermatol 2004; 3: 401-407.

19. Thompson SC, Jolley D, Marks R. Reduction of solar keratoses by regular sunscreen use. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1147-1151.

Sun exposure

Skin cancer